After a career in software development and earning two academic degrees, Bob found that his natural mode of thought is stitching together diverse intellectual threads, not axiomatic deduction. The psychology of thinking and the operations of the mind fascinated him prior to joining Mensa four decades ago. He has studied neuroscience, cognitive science, and philosophy not a specialist, but as a generalist.

Sometimes, it’s hard to trace where an interest arises, but his interest in the human brain and its relation to physical reality has certain high points that follow.

Partial Information

In 1979, sitting at his work desk faced with a large sheet of blank paper, he mulled an off-the-cuff comment to a fellow programmer: “It’s a mark of intelligence when a person can figure out a word seeing on part of the word.”

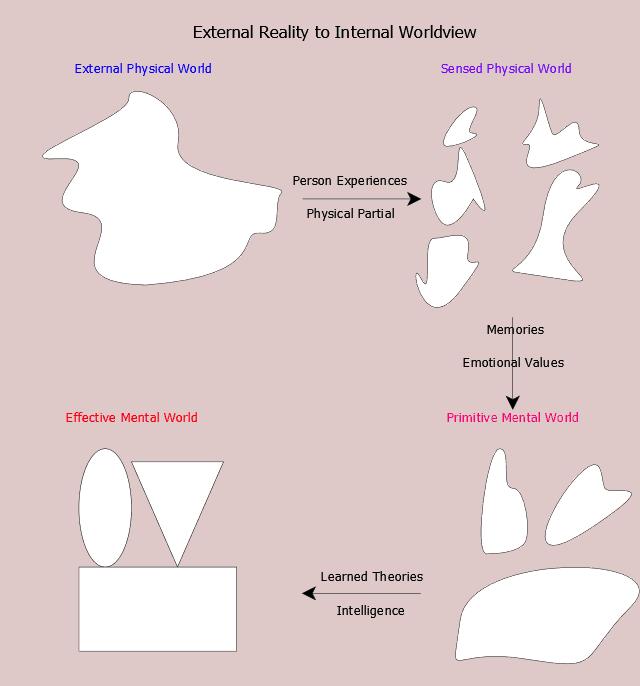

He floated a bunch of ideas on the deskpad. The figure below (External reality to internal worldview) is a dressed up version of that early attempt to understand the relationship between external reality and internal worldview.

Everything we know starts with sense data. We use memories and emotional values to arrange our world we care about. Knowledge and creativity bridge the gap from start to finish. But the mechanism which provided this creativity was elusive. Also, why are some people so rigid in their interpretations and others so free?

Simplification Rules

Without understanding how these operations occurred, certain steps appeared to occur.

- The complexity of environmental situations are simplified before we apply logic.

- Categorized occurrences cause us to think of other occurrences that share much of those categories, but not all.

- We smooth out objects and relationships to fill in the gaps of our knowledge.

Neural Networks, Artificial

In 1992 a class on Artificial Intelligence at The Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Lab, showed a new way to condense information. Little artificial neural components which had multiple inputs, processed them with a simple algorithm, outputted an answer, and then adjusted the network according to the deviation from the desired.

Backpropagation sort of worked, but it demanded an overseer, a set of good answers to calculate the errors to be propagated backward. That was interesting, but exceedingly unlikely as an explanation of how the human brain works. However, the idea of neurons as simple processing units was planted in his brain. At work, he gave a presentation on neural networks to the technical staff. It stressed the observed phenomenon of the brain, like speed of neurons, avoiding the lack of a neural mechanism which could account for processing the raw sense data.

Maureen Caudill and Charles Butler covered numerous neural network types in Understanding Neural Networks, but he was too busy with work and home to explore it thoroughly at the time. Instead he stored the notes in a folder, “Artificial Neural Networks,” for later investigation, after retirement.The Mind in the Net

His quest for growing his knowledge never flagged. Books on neuroscience, cognitive science, and biological science were a steady diet. Books that influenced his ideas are listed in Works Cited.

Early in 2006, I bought Manfred Spitzer’s The Mind in the Net. He introduced semantic maps, Kohonen artificial neural networks with their self-organizing property, and a sober development of brain processes.

The Finite Mind

He slowly developed the idea that, although the brain has billions of neurons with thousands of interconnections between them, the existence of a limited working storage meant that thoughts went through a narrow sieve at times. Although our brains could hold and remember vast amounts of information, when it came to making decisions, only a subset of that information was available at any time. Another aspect is the locus of interest a person has, through which attention rotates. The Finite Mind is somewhat after the main argument of Mental Construction.

In 2011, finally retired, he went through his hanging folders, getting excited once again about how the flux of external reality becomes stable objects in my mental world. Trying to bring the ideas into sharper focus, he saw much remained to learn, but he had time.

As mentioned above, he is a generalist, not a specialist in any of the areas discussed here—neuroscience, cognitive science, philosophy, or psychology. He is not consumed with the latest research questions unique to a specialty, but fascinated with the operation of the human mind and how that answer relates to issues in psychology and philosophy.

Contact the author at rhamill2004@yahoo.com for comments or corrections to Mental Construction.

Burning Thoughts, his blog, allows an outlet for political, economic, and science in daily life posts.