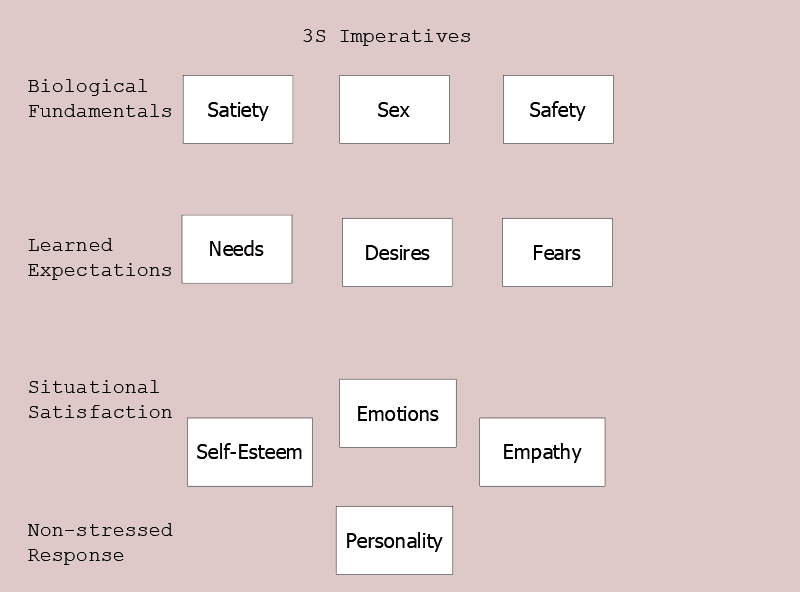

| 3S Imperatives | Uncertainty | Ethics |

What do knowledge and uncertainty have to do with the physical world? The physical world is a world of potential benefits and threats. Knowledge defines and circumscribes what potential benefits and threats you see in the world. A person has to decide how to react to the external world. It’s essential to realize all knowledge is not created equal.

- Some things we know absolutely. We have seen certain facts ourselves. Your desires and fears are yours whether other people agree with them or not. They are your truth.

- Much more we are told are true, by family and friends. Of these facts, situations, explanations, and beliefs, we can assess the relative truth of the assertions, because we have shared experiences with these people. Thus we can gauge their second-hand reports by their handling of common experiences. Perhaps they exaggerate or underplay or care about different things. We can adjust (imperfectly) for these differences.

- Vast stores of information come to us through teachers and from media. Teachers make an effort to tied their material to everyday life, but often, we don’t share a manifold of common experiences to guide our assessment of what they relate to us—their theories of history, social reality, economics, science, psychology, etc. The distance between media reports and our ability to gauge their trustworthiness is even greater.

Internal Worldview

To better examine the role between knowledge and uncertainty is to consider the internal worldview we use to made decisions. These decisions, not based directly on external reality, but on our internal view of that external reality.

We make choices that arise from our internal worldview (mindset often has a different connotation) to satisfy our needs, desires, and fears. As discussed earlier, our internal worldview is intrinsically colored by biological imperatives. Social aspects also come into play.The age at which you learn things makes a difference in your mental worldview. That is, not all pieces of your worldview are assembled according to the same dynamic. Your family’s worldview becomes paramount as you leave infancy. Their influence is strongest on the values you use in manage personal relationships. When peers rise in influence, their effect is mitigated by the beliefs you have already developed, but your peers also expose you to facts and beliefs beyond those assumed in the family sphere. Similar expansion of worldview occurs in classrooms and then by media outlets. More on this in Development to the Adult Mind.

We build our knowledge structure in a manner that recognizes our needs, desires (goals) and fears.

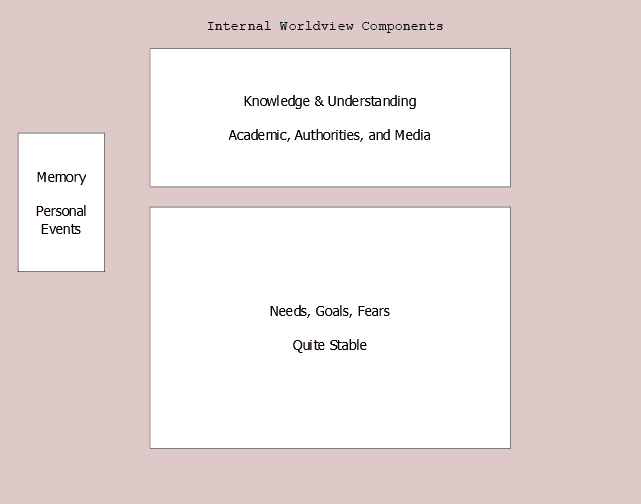

Internal Worldview Components

A person’s internal (mental) worldview has three basic components (Figure 5.1). Memories relating personal events (called episodic memory) are base rocks of our worldview. Knowledge and understanding of relationships between elements of external reality are essential parts of our world view and decision-making process; however, the reliability of our knowledge varies from nearly certain to hopefully true to riddled with exceptions. We often must hope exceptions don’t invalidate our use.

Lastly, our needs, desires, and fears—a combination of our unique genetic inheritance and personal experiences—control our attention towards external reality as well as focus the interpretation of events.

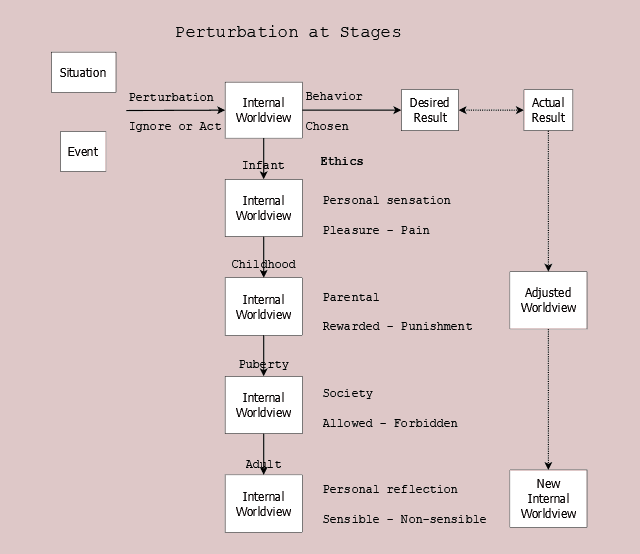

Events and Perturbation

One’s internal worldview is usefully considered as a steady state system with perturbations. Events are perturbations to be understood within our internal worldview. Events are not experienced independent of our understanding. This bullet-point discussion of Figure 5.2 provides the relation of age-related reactions to events, with the different moral code used in evaluating behavioral choices. Of course, the internal worldview may be modified to accommodate very significant events when the current worldview presents inadequate choices.

- New experiences are processed and understood relative to one’s internal worldview, which undergoes significant shifts according to one’s progress towards maturity. See Learning for more details on the relation between stage and driving forces in decision-making.

- The situation is broken into events of interest (perturbation) and background (understood by concepts of existing worldview).

- Events of interest are assessed as to their ability to satisfy one’s needs and desires and to lessen one’s fears.

- From one’s knowledge of relationships between events and consequences, various behavioral responses present themselves.

- The behavioral response that maximizes the sum of satisfying one’s needs and desires and lessens one’s fears is chosen and performed.

- Depending on the result of the behavior, a change may be induced in one’s knowledge and perhaps even to desires or fears. The change in a deeply held piece of knowledge or desire or fear can shake one’s worldview–like an earthquake, rattling one’s faith in the pillars of belief.

Also broken out in Figure 5.2,

- As an infant, our ethics (selection of behavioral choice) are driven by immediate satisfaction–the need to satisfy hunger and the desire to achieve physical comfort. Pain and pleasure.

- As a toddler and youngster, our ethics are adjusted by parental rules–dictates that certain behaviors are rewarded while others are punished. Reward and punishment

- Once puberty is reached, our ethics as well as our interests change. Our knowledge about alternative ethical regimes grows dramatically as we experience life further outside the family circle. The physical and physiological changes accompanying puberty cause the importance of sex to leap in our estimation of situations, events, and situations. Approval and disapproval

- In maturity, many of us reflect on the difference between the claims of society and the actuality of events, which can result in partial rejection of societal norms. Reasonable and non-reasonable

Development of one’s knowledge upon we depend for our decision-making, relies on our experiences and the abilities of our memory.

Memory

Mental Construction focuses on memories that are more processed. Facts and experienced events are the most obvious. These memories have features, usually are only partially recalled. They also bring further memories to conscious awareness.

Memory is not an exact video of past events. It is a personalized assessment of a past event, a weighing of features according to one’s interests and understanding. One’s needs, desires, and goals affect what we remember of events. One remembers what is important to one’s interests.

But let’s come back to memory. As Alan Baddeley says in Your Memory (p 10–11), discussing the physical basis of memory.… However, many of the claims for an understanding of the molecular basis of memory … have been shown to be premature. … There is no doubt progress is being made in this important area, and that one day there may be a very fruitful collaboration between the experimental psychologist and the neurochemist. Today, however, there is little area of overlap.

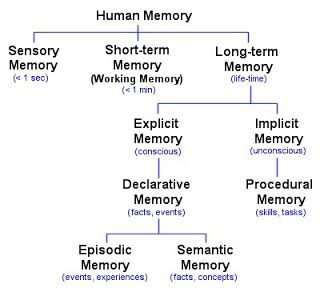

Baddeley’s book also gives Figure 5.3, an important delineation of separate uses of the term ‘memory.’ Episodic memory previously mentioned in the bottom leaf of the left. The broadness and speed of an individual’s working memory, the middle entry on the top, will be discussed for its crucial role in decision making.

- Sensory memory has three main subsystems. Sensory data can have a lag of 1/2 second or more until it is registered by the brain. These subsystems retain that much sensory input supporting continuity of sensation as well as allowing attention (or inattention) to further analysis.

- Visual sketchpad

- Phonological loop

- Haptic (touch)

- Short-term and working memory is the term used for two distinct functions.

- Short-term memory is the gateway to eventual long-term memory.

- Working memory provides the arena for a number of thoughts, facts, and theories to be considered together.

- Long-term memory is what is commonly referred to as memory. It has its own distinct components.

- Explicit memory (declarative memory) is the repository of consciously remembered facts.

- Episodic memory contains memories of our life events, our experiences.

- Semantic memory is store of our learned facts, concepts, theories, etc.

- Implicit Memory (procedural memory) holds the skills of routine behaviors and tasks we have mastered. Tying our shoes or riding a bike without conscious attention to the activity are examples of using procedural memory.

- Explicit memory (declarative memory) is the repository of consciously remembered facts.

Memory is not unlimited, especially working memory which we used when focusing on problems and decision making. Torkel Klingberg in The Overflowing Brain, subtitle Information Overload and the Limits of Working Memory, draws a clear connection between working memory.

Knowledge

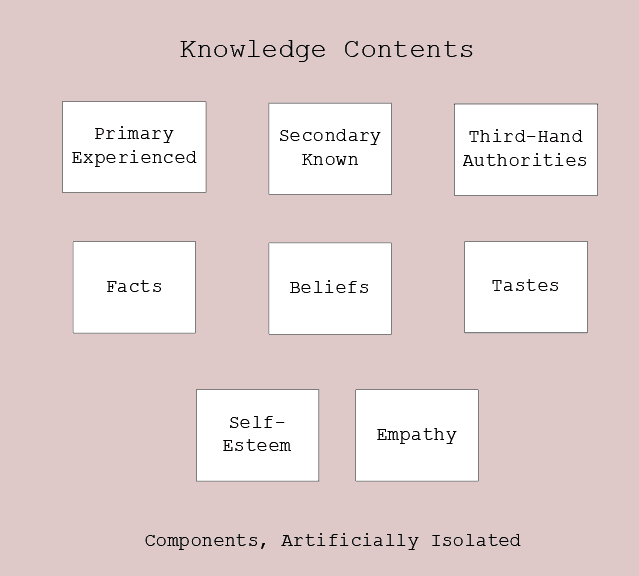

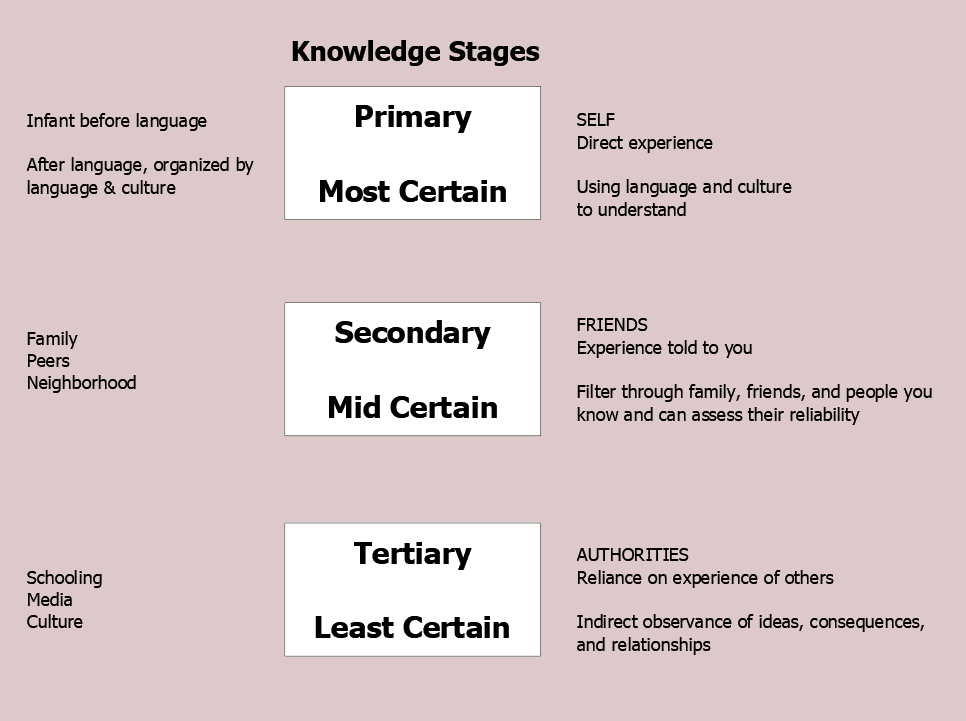

Knowledge has structure. Figure 5.4 separates those things we know.

- Into three sources of knowledge (primary, secondary, and tertiary) with declining certainty.

- Proceeding down, knowledge is categorized by its type: facts, beliefs, and tastes.

- Facts are events that have occurred.

- Beliefs, which also includes theories, are the way by which we combine various facts and assumed facts into a framework that allows us to explain why those events happened as well as predict what might happen in the future.

- Tastes, preferences that are accepted as being beyond dispute, as in food, drink, hobbies, pastimes, etc.

- Self-esteem, a measure of the internally-developed sense that one is worthwhile as well as one’s likelihood of achieving success with one’s goals. As one experiences successes and failures with behavior choices, an overall measure of likelihood of future success in any endeavor is accumulated. This self-esteem colors the certainty of one’s grasp of worldly facts, interconnections, and therefore expectation of personal success.

- Empathy, a measure of a person’s sympathy for another’s plight. We are social animals, living in groups and acting in coordination or discord. People’s experiences, in conjunction with their innate genetic makeup, result in a caring (or uncaring) of other people’s condition.

Both self-esteem and empathy are used in decision-making. To understand the origin of these two factors, we need to first discuss the 3S Imperatives.

3S Imperatives

The 3S imperatives (Satiety, Sex, and Safety) shape our internal worldview (Figure 5.5) by directing our awareness and attention toward fulfilling these fundamental demands.

Satiety is the satisfaction of the physical needs of our body. It originates in the biological drive for homeostasis, first exhibited when the vertebrates emerged more than 500 million years ago. Homeostasis is the automatic search for the level of bio-chemical ions that allows the organism optimal physical performance.

Sex first arose as a motive force for behavioral choices more than 1 billion years ago. If homeostasis is not demanding immediate action, sexual desire can direct our interest and action.

As memory became an important feature of higher animals, links between behavior and result developed. Behaviors with bad results could be learned to be avoided.

Safety, individual preservation, elevated immediate flight-or-fight reactions to a feature of decision-making. Now they could be applied to situations that might arise from decisions.

Since we are unsure of what the future will bring and because we are weighing three primitive factors (the 3S Imperatives), there is a vast mixture of partial satisfactions that can result. Our uncertain anticipations are organized into more general terms as needs, desires, and fears. The manner in which they interact with our situations are labeled emotions.

Emotions result from choosing a behavior that maximizes the sum of the satisfaction of our 3S imperatives, constrained by the limit that only one behavior can be chosen. Usually the 3S Imperatives are each, only partly, satisfied.

Personality is the semi-stable emotional collection of behavioral responses we make from the choices available. The strengths of the 3S’s in an individual are relative stable as is the physical context these days. This leads to a routine selection of certain behavior responses, personality traits.

However, sometimes the behavior chosen fulfills one imperative and frustrates one or both of the others. That is upsetting and reverberates in our mental worldview, resulting in adjustments to the importance we attach to related content.

Sources of Uncertainty

As often mentioned, all knowledge is not of the same certainty. Some facts, such as remembering that you hated tomatoes when you were five, are much more certain than your belief that the Roman Empire fell because of barbarian raids or that the stock market will rise.

Take a minute to look at the separation of knowledge shown in Figure 5.6. Because stages occur sequentially, they build upon earlier learning. An error or incompleteness in early knowledge will often manifest itself as tortured or unreliable subsequent learning.

Of course, primary information continues to accrue while we are learning language, interacting with our peers, and digesting other people’s ideas; however, the older, deeper, and more immediate the knowledge the more difficult it is for a later stage to dislodge it.

In these bullet points referring to Figure 5.6, structural organization substitutes for verbal connectives. The purpose is to exhibit an example of associations as they might follow in the non-verbal hemisphere.

- Primary. Immediate. You experienced it

- Knowledge of self. Wants, needs, likelihood of satisfaction

- Firm knowledge. Positive aspects of your experiences, despite partial and idiosyncratic factors

- Once language is acquired, verbal categories provide a ready template for organizing experience. Directly in the verbal hemisphere and indirectly via comparison across the corpus callosum.

- Secondary. Limited. Told by person you have shared experiences with

- Knowledge from others

- Fairly secure in our assessment of its accuracy. Through direct experience, you know who exaggerates, who underplays, who shares your opinions, who doesn’t.

- Tertiary. Societal. Observed and instructed on society, academia, and media

- Knowledge of how things are linked together. Explanations of the past, predictions of the future

- Academic and scientific theories.

- Some theories and facts you can’t evaluate directly. You must decide which authorities you will trust.

As we get further from personal experience, we have progressively less confidence in the knowledge we gain. Yet we still have to act, forcing us to rely on information and knowledge about which, in reflective moments, we have doubts about.

Religion, as well as other theories, comes to our awareness at multiple times (and stages) of our life. When they first are experienced makes a difference to the firmness with which we hold their value.

Linguistic Items

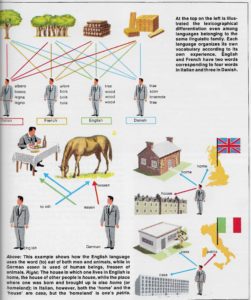

As we learn language, words become building blocks that we use to understand and describe the world. In Figure 5.7, words are used in different manners to describe similar objects.

The fundamental observation is that, no matter the language, words shape our internal worldview, the Weak Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis

In the top example in Figure 5.7, English speakers can store information about a group of trees, a cord of logs, and finished products all with the word “wood”. It takes additional words to delineate the objects. Additional words consume mental capacity.

However, we shouldn’t forget that the funnel of working memory constrains us to some 7 to 10 elements at a time. Thus, the more capacity reserved for description, the less available for logical deduction. One’s language can affect the utility of working memory on particular situations.I’d also be remiss if I didn’t mention that we use the term “fact” in several contexts, thereby obscuring the uncertainty and subjectivity of much knowledge. This greatly impacts discussions in which contentious positions exist. Also, facts which indubitably occurred are quite different than conclusions based on fallible human understanding. Facts need to be distinguished from explanations, evaluations, and predictions.

Ethics

Investigating decision-making is a goal of Mental Construction. Decision-making reveals one’s ethical system–as well as one’s trade-off between immediate satisfaction and delayed gratification. Lawrence Kohlberg developed a system of ethical development, the fundamental element is that one’s moral system is not static. I’ve defined into ethical stages aligned with the age stages used in Development of the Adult Mind.

- Birth to language acquisition. Does it feel good or does it feel bad? (pleasure principle)

- Language to personal memory. Is one punished or rewarded for the action? (might makes right)

- Personal awareness to puberty. Does neighborhood allow it? (permissive)

- Teen to early independence. Do society’s rules allow it? (logical)

- First responsibility to brain’s full operation (late 20s). Do rules align with stated purposes and goals? (reasonableness)

These are the stages in order. Not everyone goes through all five ethical stages. Many are satisfied with their results at an earlier stage. The moral stage we are in when we acquire certain knowledge affects how we us the 3S imperatives in developing worldview.

Next, we go to neural connections where you will see how, by their very nature, neurons force internal order upon an unruly reality.

Free Speech and Mindset The impact of fake news and how to minimize it

Nature-Nurture Neural aspects of critical learning periods